History’s Great Women: Women of the United Kingdom

For centuries, the idea that history is written only by the victors of conflict has been popularly held by scholars and politicians alike. In truth, however, while many pieces of history were tragically lost to the fallout of wars and hegemony, other stories persisted, often through the dedicated efforts of individuals who knew the value of the stories they could tell.

Throughout much of the history of the world, the history of women was ignored, belittled, or erased. Nonetheless, stories of the great works and lives of women have been preserved by those with the wisdom and the fortitude to tell the sides of stories some would prefer to be forgotten.

In the history of the United Kingdom, countless women have stood up to challenge the troubles of their times, and the influence of their work has been felt long after their passing, sometimes for millennia.

A brief profile of a small selection of these women follows below, in hopes that their stories will live on in readers.

Joan Clarke

Member of the Order of the British Empire and skilled codebreaker Joan Clarke Murray was a Cambridge graduate in mathematics, earning the top honors available at the school at the time of her graduation. Despite her incredible mathematic aptitude, Joan Clarke was denied a formal degree, which Cambridge refused to issue to women until the late 1940s.

At the beginning of World War II, one of her classmates, a man by the name of Gordon Welchman, invited her to join a project he was part of known as GCCS, “Government Code and Cypher School,” located at Bletchley Park. This group of mathematicians was brought together by the government to help break the so-called “Enigma Code,” which German leadership touted as impossible to break.

For some time, Joan Clarke was limited to non-cryptology roles, instead being assigned with the other women of the project to administrative and clerical tasks. Regardless of her limitations in role, she quickly outgrew the position and came to master a process known as Banburismus, developed by GCCS colleague and famous computer scientist Alan Turing.

For some time, Joan Clarke was limited to non-cryptology roles, instead being assigned with the other women of the project to administrative and clerical tasks. Regardless of her limitations in role, she quickly outgrew the position and came to master a process known as Banburismus, developed by GCCS colleague and famous computer scientist Alan Turing.

During the war, she was the only woman to ever master this process, and, as a result of her remarkable skill, her supervisors promoted her to the position of “linguist” within GCCS. This was a loophole designed to earn her slightly more pay, since she had been (and still was) paid considerably less than male colleagues of the same and lower ranks.

Clarke eventually rose to the position of Deputy Head in 1944, the highest position allowed to any woman in the program. She was refused further promotions.

During her time at Bletchley Park, she became very close friends with Alan Turing. Working together frequently, Clarke and Turing made significant contributions to both British intelligence agencies and cryptology as a whole.

Joan Clarke’s mastery of mathematics contributed heavily to the breaking of the code used to encrypt Nazi war messages, which influenced the British fight against Nazi forces to degrees that, to this day, cannot be fully quantified.

Mathematics and algorithmic codes are now used in a broad range of computational devices and are often taken for granted in the 21st century. Joan Clarke was notably ahead of her time in this field and the real recognition for this feat has only really come into the public spotlight over 50 years after she was carrying out her important work.

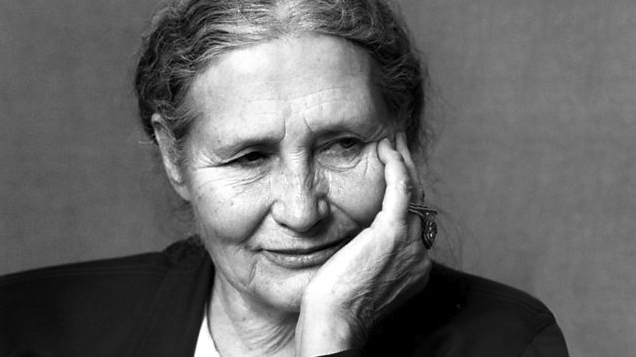

Doris Lessing

Born in late October of 1919 in the city of Kermanshah, Iran to British parents, esteemed author Doris Lessing’s early life unfolded across not only multiple countries, but multiple continents. At the age of six, Lessing’s family moved to Zimbabwe, which was, at the time, colonised by Britain under the name of Southern Rhodesia.

In Zimbabwe, Lessing’s family attempted to live a simple life on a farm, but the farm ultimately did not turn a profit. Doris left the farm in her mid-teens to work and eventually moved to Britain to pursue work as an operator. Having been educated up to the age of 13 in Zimbabwe, Lessing took her education into her own hands and began to pursue writing on her own time.

In the early 1940s, Lessing took interest in Left politics and writing, becoming involved with the “Left Book Club,” a publishing firm that was heavily influential in the British left-wing of the mid-1900s.

Her interest in socialist politics helped motivate her move to London in 1949 to pursue writing, as well as a number of other significant events of her life. Inspired by her convictions, she was an outspoken activist who campaigned against nuclear weapons and apartheid. Her views on Apartheid resulted in both the colonial governments of South Africa and Zimbabwe banning her from access to the country.

Her strong left-wing beliefs did not stop her from criticising other left political groups. She was incredibly outspoken against many of the warlike actions undertaken by the Soviet government of Russia.

The novels she wrote were incredibly successful to the point that multiple of the most prestigious awards in the country were offered to her.

She turned down many of the British awards as a political statement; she did not believe in accepting awards tied to an imperial government she didn’t support. However, she did accept the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2007.

Following her acceptance of the Nobel Prize, she became the oldest winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature and the 11th woman to receive the award.

Doris Lessing’s work approached social issues with a fearlessness and lack of censorship that was incredibly rare in her time. Furthermore, her work challenged many of the political assumptions of the time, both in the fact that she had such incredible success despite social punishment for her views and gender and in the fact that her work pulled no punches in challenging the remnants of colonialism across the world.

Boudica

Both an important historical figure and a folk hero of the United Kingdom, Boudica was responsible for taking lead of the Iceni Celtic Tribe in a revolt against the overwhelming legions of Rome.

Boudica led the Iceni tribe to revolt after Roman forces annexed their kingdom, which had previously been an independent ally to the Empire of Rome led by Boudica’s husband, Prasutagus. Upon Prasutagus’ death, his will indicated that the kingdom of the Iceni should have fallen to joint rulership by his daughters and Rome, as it had been while he was king.

Roman troops ignored the orders and, by the account of the Roman historian Tacitus, Boudica and her daughters were severely tortured.

In response, Boudica united the local Celtic tribes, including the Iceni, and led them to war. Queen Boudica’s campaign met early success, with her forces destroying Colchester, London, and St. Albans. The clashes at London and St. Albans were extremely bloody for both the Roman and Celtic forces, though the Roman legion ultimately retreated.

At the height of Boudica’s revolt, Nero, the Emperor of Rome, seriously considered a full retreat from the British Isles. However, the Roman Governor of Britain, Suetonius Paulinus, ultimately exhausted her forces, defeating her army at the Battle of Watling Street. Boudica herself would never capitulate to Rome, dying before the Romans were able to wrest control of Britain again from its native people.

The historian Tacitus asserted that she took her own life rather than allow Rome to have victory over her, while the other major Roman historian to write of Boudica, Cassius Dio, asserted that she died of illness.

The Roman accounts of Boudica are the only ones that exist in full, and, as a result, are somewhat tainted with the biases of Roman society including Cassius Dio’s description of her as “possessed of a greater intelligence than often belongs to women” (Source: Peter Keegan’s “Boudica, Cartimandua, Messalina, and Agrippinia the Younger.

Independent Women of Power and the Gendered Rhetoric of Roman History.”) Regardless of some of the implicit cultural biases present in the writings of the Roman historians, both Cassius Dio’s and Tacitus’ accounts do not portray Boudica’s revolt as illegitimate; both historians attest to her rightful heirship, royal ancestry, and martial prowess.